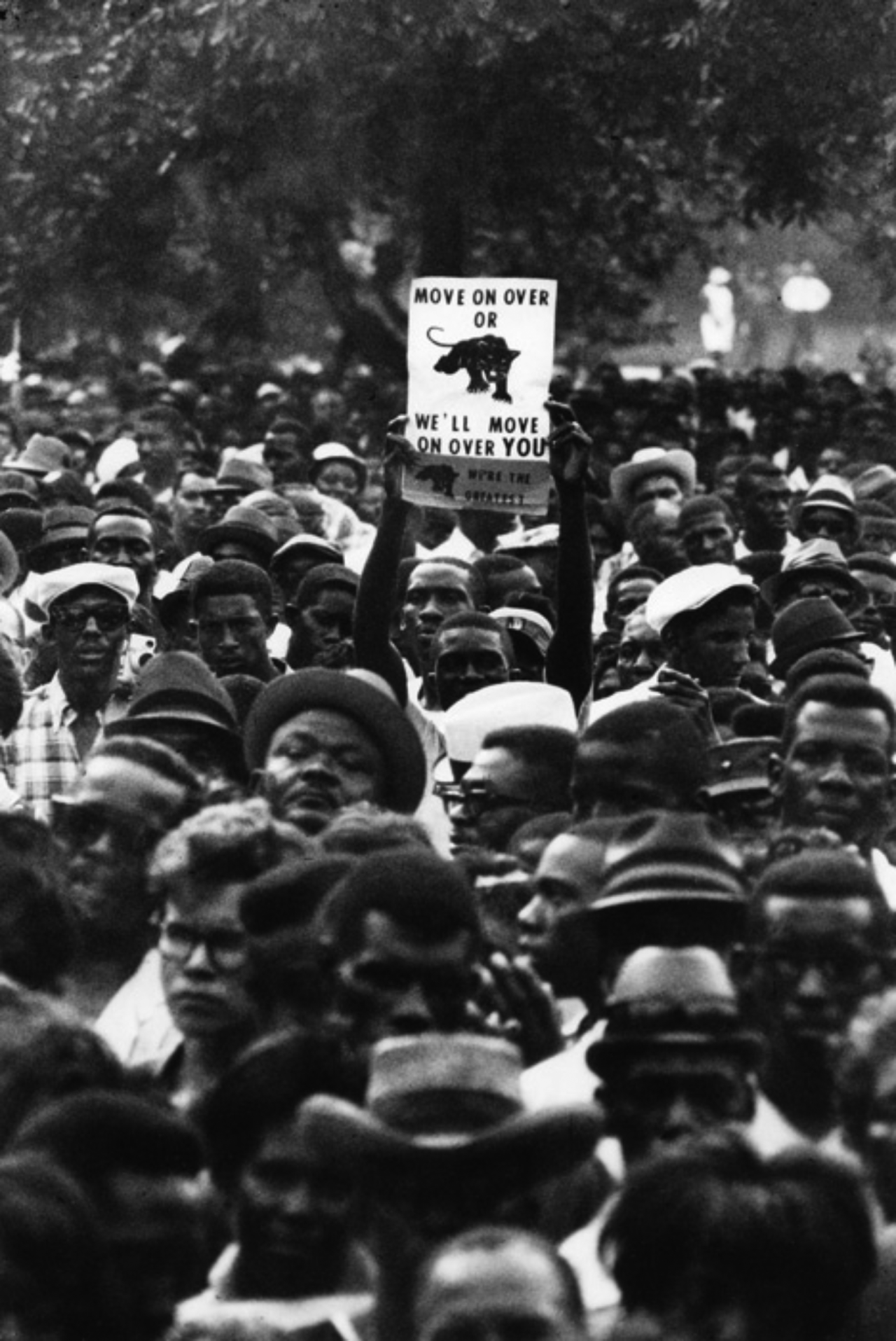

Black Panther Party members rally in 1968

I have no doubt that the revolution will triumph. The people of the world will prevail, seize power, seize the means of production, wipe out racism, capitalism.

Huey P. Newton (1973)

Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in Oakland, California. Newton and Seale met at Merritt College and founded their group in October 1966.

1966

Watch Black Panthers (1968), a short film by Agnes Varda Source

Protest for Civil Rights, photograph by Flip Schulke Source

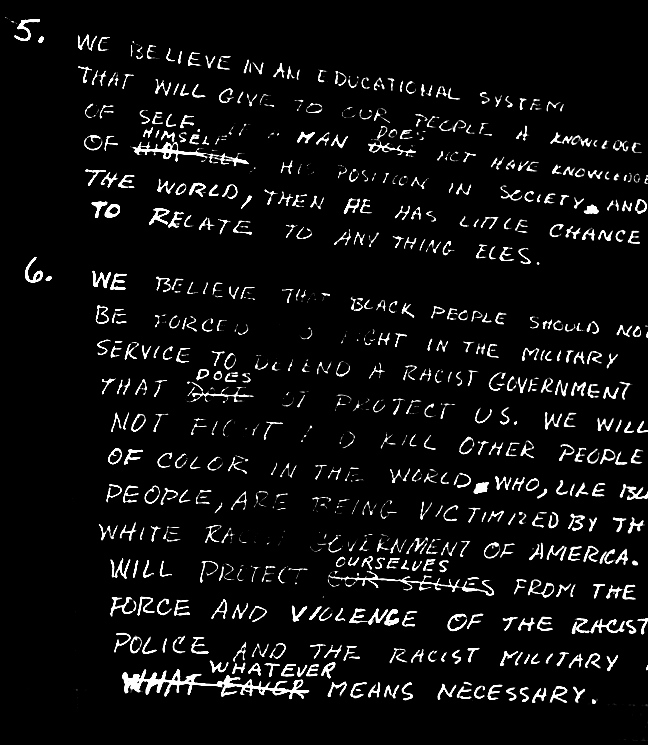

The group set its political goals in a document entitled the Ten-Point Program, calling for better housing, jobs and education for African Americans alongside a call for an end to economic exploitation, an improvement of life in Black communities and an end to police brutality.

The fifth point of the draft of the Black Panther Party’s original 10 Point Program, written in 1966 by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton (and handwritten by Seale), titled “What We Believe.” Source

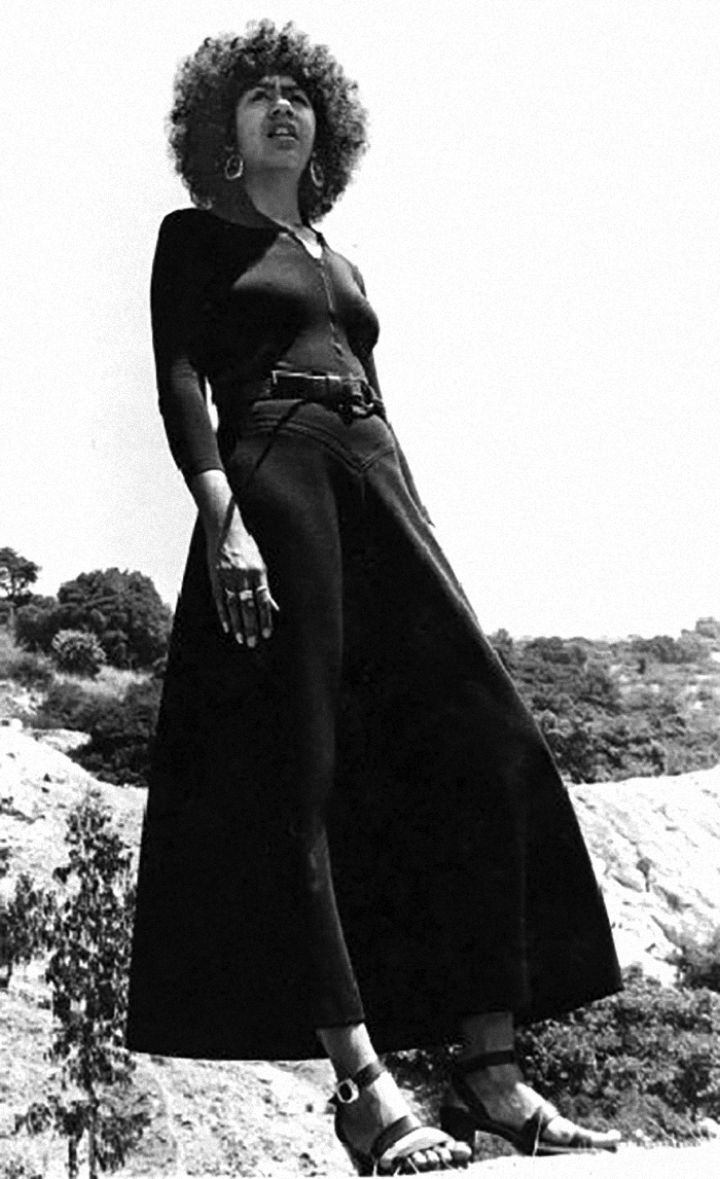

Ericka Huggins in California in 1971. Source

Love is an expression of power. We can use it to transform our world.

In the 1970s, Newton aimed to take the Panthers in a new direction emphasising democratic socialism, community interconnectedness and services for the poor including free lunch programs and health care.

- Panther Profiles

-

Huey P. Newton

Co-founder of The Black Panther Party

“The revolution has always been in the hands of the young. The young always inherit the revolution.”

Huey P.Newton was a revolutionary activist best known for founding the militant Black Panther Party with Bobby Seale in 1966. He was died on August 22, 1989, in Oakland, California, after being shot on the street.

Huey Percy Newton was born on February 17, 1942, in Monroe, Louisiana. Newton helped establish the African American political organization the Black Panther Party, and became a leading figure in the Black Power movement of the 1960s.

-

Bobby Seale

Co-founder of The Black Panther Party

“You don’t fight racism with racism, the best way to fight racism is with solidarity.” Bobby Seale is a political activist and was co-founder and national chairman of the Black Panther Party.

As cofounder and Chairman of the Black Panther Party, Bobby Seale was an important leader of the Black Power movement. Born in Texas, Seale joined thousands of African Americans when his family migrated to Oakland, California during World War II.

Inspired by Malcolm X, independence movements in Africa, and anti-colonialist intellectuals such as Frantz Fanon, he founded with [Huey P.] Newton in 1966 the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

While working at a War on Poverty program, he and Newton wrote a ten-point program that outlined the outlook and goals of the BPP.

-

Emory Douglas

Revolutionary Artist & Minister of Culture, Black Panther Party

Emory Douglas was a member of the Oakland and San Francisco chapters of the Black Panther Party. He was the revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture for the Party and oversaw art direction and production of The Black Panther, the official newspaper from 1967 to 1980.

Emory Douglas was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1943. His family moved to Oakland when he was eight due for health reasons and a better climate. After some trouble with the law Emory spent 15 months at the Youth Training School in Ontario, California working in the print shop. This provided the basic training in typography, illustration and logo design. Later he enrolled at City College of San Francisco and it was there he began to explore the combination of art and message.

In March 1967, when Douglas met Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, founders of the newly formed Black Panther Party. “After that meeting, I told them I was interested in joining the party. I began catching the bus to Oakland, hanging out with Huey and Bobby and going on patrols with them,” says Douglas.

At civil rights activist Eldridge Cleaver's apartment, where Seale was working on the inaugural issue of The Black Panther, Douglas offered his design skills. He realized The Black Panther needed potent images to cut through the high illiteracy rates in poor communities.

-

Ericka Huggins

Human rights activist, poet, educator, Black Panther Party leader and former political prisoner

"On developing a description for the Black Panther Party, Ericka Huggins says. “We know the party we were in and not the entire thing. We were making history, and it wasn’t nice and clean. It wasn’t easy. It was complex.

As an activist, former political prisoner & leader in the Black Panther Party, educator & student I’ve devoted my life to the equitable treatment of all human beings—beyond the boundaries of race, age, culture, class, gender, sexual orientation, ability and status associated with citizenship.

I spent 14 years in the Black Panther Party—the highlight being my eight years as Director of the renowned Oakland Community School from 1973-1981. During that time I became both the first Black person & the first woman appointed to the Alameda Co. Board of Education."

– Extract from Ericka Huggins' Bio

-

Elaine Brown

Minister of Information & Chair (1974–77), Black Panther Party

In 1974, Elaine Brown became chair of the Black Panther Party. She was also Minister of information. Elaine grew up in the ghettos of North Philadelphia and now lives in Oakland. Elaine is also a musician and recorded two albums. She is CEO of a non-profit Oakland & the World enterprises dedicated to not-for-profit cooperative businesses set up by formerly incarcerated people and others facing barriers to economic survival.

– Sourced from Elaine Brown's websiteWhile leading the Party she contributed to the campaign of Lionel Wilson, who became Oakland’s first black mayor. She also worked to establish the Black Panther Party’s Liberation School. However after the return of Huey P. Newton, Elaine Brown stepped down from leadership and the Black Panther Party due to concerns regarding sexism and ensuing violence.

Presently, Brown lectures at colleges and universities, as well as at numerous conferences, while still maintaining her efforts as an activist.

– Sourced from archives.gov -

M Gayle Dickson

Graphic Artist, Black Panther Party

M. Gayle Dickson, also known as Asali, was the only woman graphic artist for the Black Panther Party Newspaper between 1972 and 1974. Dickson was born in Berkeley, California on June 27, 1948.

In 1966, she graduated from Fremont High School and attended Laney Community College where she studied painting. A year later, she transferred to Merritt College, a hub for black student political protest, and learned about African cultural heritage through African masks. While there, she also joined the Black Student Union and engaged in a protest against police brutality at the Housewives Market in downtown Oakland after police assassinated Bobby Hutton.

Her images [for the Black Panther newspaper] often focused on women and children to critique capitalism and urban poverty.

– Sourced from blackpast.org

-

Mama Charlotte Hill O'Neal & Pete O'Neal

Black Panther Party, Kansas City Chapter

Charlotte Hill O’Neal, aka Mama C, was a member of the Kansas City chapter of the Black Panther Party before she went into exile with her husband Pete O’Neal in Tanzania. Together, the two have worked in community development and founded the United African Alliance Community Center. She is a visual and spoken word artist, musician, longtime community activist and performs her music and poetry at events in Arusha and tours the globe.

– Source“On January 30, 1969, O’Neal, then 29, announced the formation of a Black Panther chapter for Kansas City right in the hallway on the fifth floor of Kansas City police headquarters. With over 30 supporters looking on, and some police officers, he read a list of demands, which included an immediate end to police brutality and the murder of black people. Several confrontations with the police and arrests of Panther members ensued in the following year.”

– Source -

Billy X

Veteran member and archivist, Black Panther Party

Black Panther Party (BPP) veteran member, activist, educator and archivist Billy X Jennings acted as the personal aid to BPP leaders Huey Newton and David Hilliard. In this interview, Jennings discusses the legacy of the Party within the US and outside it, the role of education in revolutionary practice, his experiences alongside Newton and other Panthers, and lessons for the current uprisings in the United States and the world.

-

Angola 3

Members, Black Panther Party

Albert Woodfox, Robert King and Herman Wallace were known as the Angola 3. They spent a combined total of 114 years in solitary confinement for crimes they did not commit. Their real “crime” was being black in the U.S. and organizing the only prison chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Most of their time was spent in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, which is located on a former slave plantation known as Angola.

Robert King was released in 2001 after 29 years in solitary, Herman Wallace was released after 42 years on October 1, 2013 and he died of cancer three days later, and Albert Woodfox saw freedom in February 2016 after almost 44 years in a six-by-nine cell for 23 hours a day.

Since their release, both Albert Woodfox and Robert King have authored critically acclaimed autobiographies and they continue to fight for reforms in the criminal justice system.”

– SourceHeroes: A conversation with Albert Woodfox and Robert King

After 40 years in solitary, activist Albert Woodfox tells his story of survival, 2019

Emory Douglas - The Angola 3, the Prison-Industrial Complex, and Abolishing Solitary Confinement -

Bobby Hutton

First Recruit & Treasurer, Black Panther Party

Robert James Hutton, also known as Bobby or Lil’ Bobby, was the first recruit to join the Black Panther Party (BPP) at just 16 years old. He became the first treasurer. In 1967 Bobby Hutton led 26 Black panthers on a march on the State Capitol in Sacromento to protest new gun laws – all were arrested. Bobby Hutton was killed by police during a shootout in Oakland on April 6, 1968. Police ambushed a car occupied by BPP members. The shootout lasted for an hour and a half. Bobby Hutton was shot more than 12 times after he had already surrendered and stripped down to his underwear to prove he was not armed.